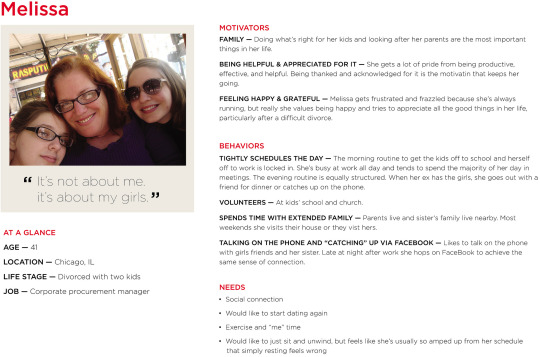

It appears to be a bio for a fictional person, meant to represent a specific type of user of your product. Typically, someone compiles a slide deck containing a handful of different personas, and that deck is presented to the team. Everyone is then supposed to “keep them in mind” during the design phase so the resulting product “works for them.”

There’s only one problem: you can do all that and not improve your product in any meaningful way.

The salient fact about design personas is that most “designers” don’t understand them and use them wrong.

— Alan Cooper, March 26, 2013

That’s a quote from the inventor of personas (and Visual Basic, among other things). The trouble is, there’s a lot of nuance to creating and using personas effectively. In my experience, it’s really easy for the team to slip up somewhere along the way. So what should we do instead?

A Useful Tip

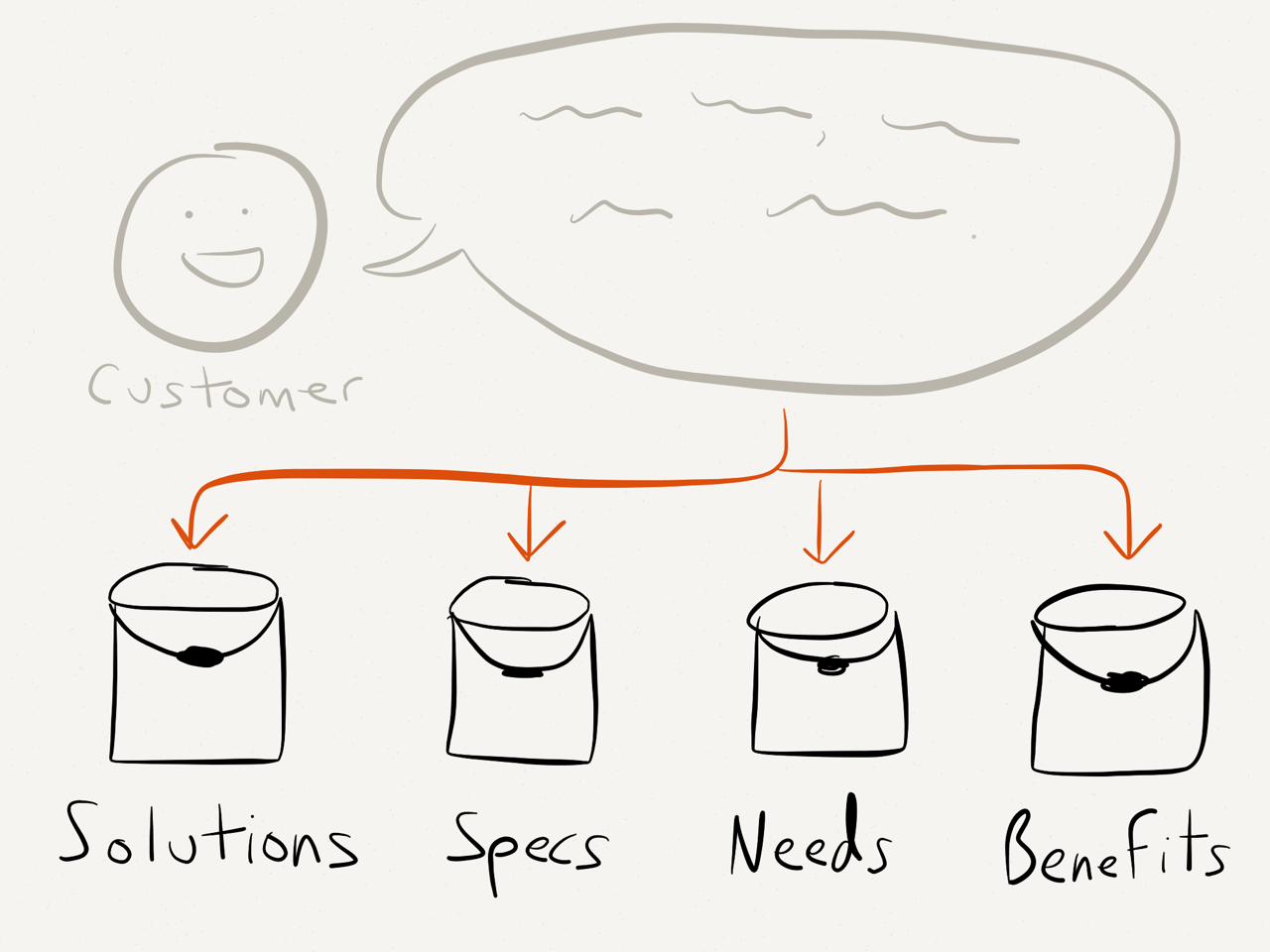

One great piece of advice came in the form of a metaphor from Jonathan Korman during CooperU’s UX for Product Managers class:

Imagine you’re setting up a tent, and you’re trying to place the minimum number of tent poles in the optimum locations to get the most coverage. The poles are your personas, and what you’re covering is your target market.

So in a health care app, for example, you might have the following personas:

Julian, a physician who only needs to use a few key features of the system, but is impatient with technology

Lou, an elderly patient who has trouble with vision and fine motor control

Carol, a nurse who does the bulk of the heavy lifting in the app while juggling a massive patient load

All three personas “stretch the tent,” applying pressure on the design. To improve the product, the team might remove some friction for the physician, increase accessibility for the patient, and build some extra power user features for the nurse.

Each additional piece work contributes to a business goal: increasing the number of customers that can be served. If each of these demanding user’s needs can be met, the product will slightly overserve everyone “behind” them who’s not as demanding.

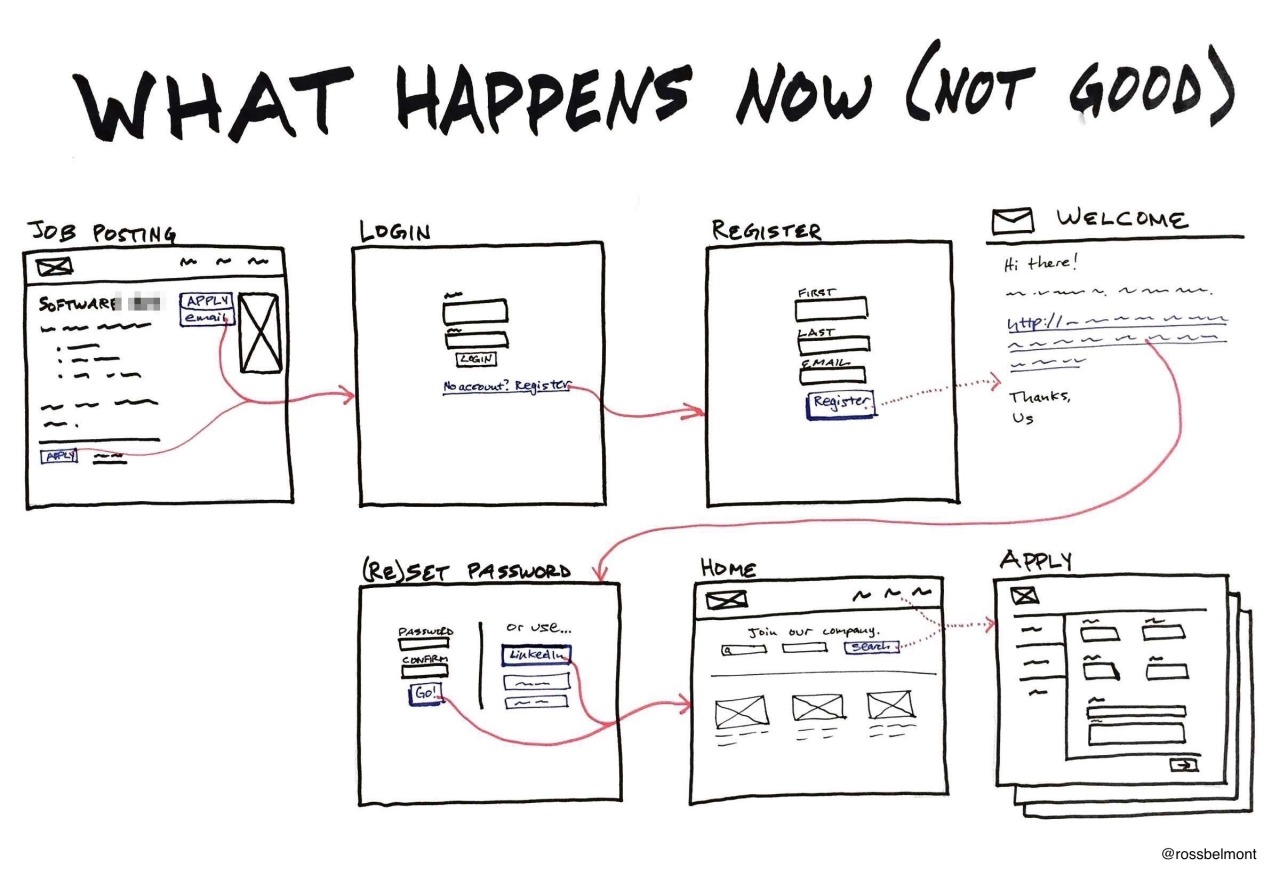

We used this technique in some recent work we did building a recruiting system. The behavior pattern we noticed was those asked to interview candidates do so “on the side” and aren’t deeply engaged with hiring. Hence, we created a way for them to view a candidate’s resume without even logging into the recruiting tool.

Meet Cornelius

MillerCoors takes this to a comical extreme with Cornelius, the lead character in a new series of ads for their Smith & Forge brand of hard ciders. Cornelius, and his extremely manly associates, enjoy a Smith & Forge beverage after a hard day’s work in the 19th century: blacksmithing, chopping down trees with an axe, and so on.