"Their customers never flinched." →

James Surowiecki:

You had tens of millions of affluent consumers. They ate out a lot. They were comfortable with fast food, having grown up during its heyday, but they wanted something other than the typical factory-made burger. So, even as the fast-food giants focussed on keeping prices down, places like Panera and Chipotle began charging higher prices. Their customers never flinched.It might seem that the success of fast-casual was simply a matter of producing the right product at the right time. But restaurants like Chipotle and Five Guys didn’t just respond to customer demand; they also shaped it. As Darren Tristano, an analyst at Technomic, put it, “Consumers didn’t really know what they wanted until they could get it.”Some of this is analogous to the recent rise of Apple as well. Certainly, there’s an element of “right place, right time”, but it’s also about shaping conditions to create that place at that time.

Few consumers can imagine new products or services they’d buy at anything but the “lowest resolution.”

What Customers Say

What do you get when you talk to customers?

I just finished a large round of customer interviews and was reminded of something in Tony Ulwick’s great book, What Customers Want.

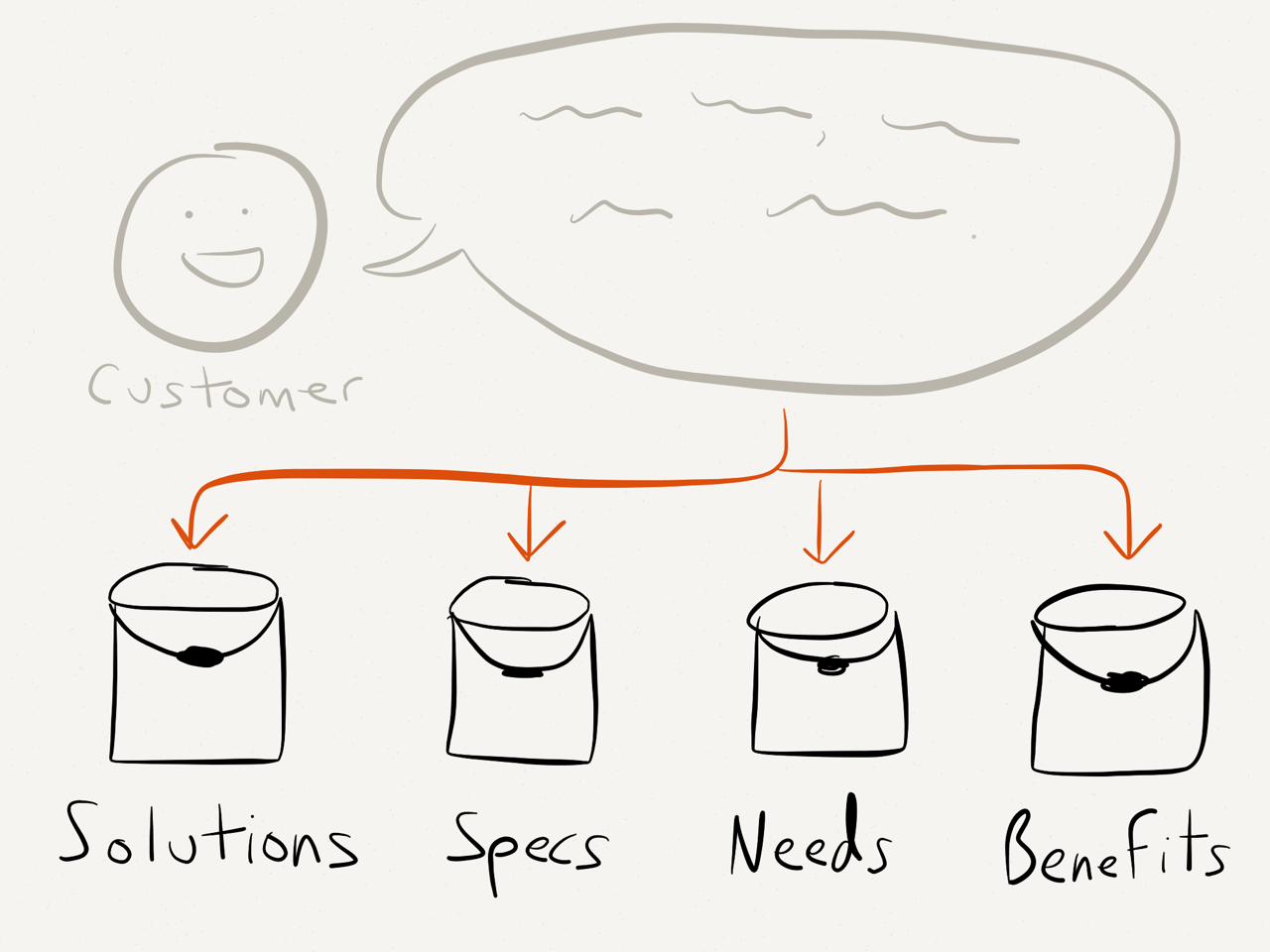

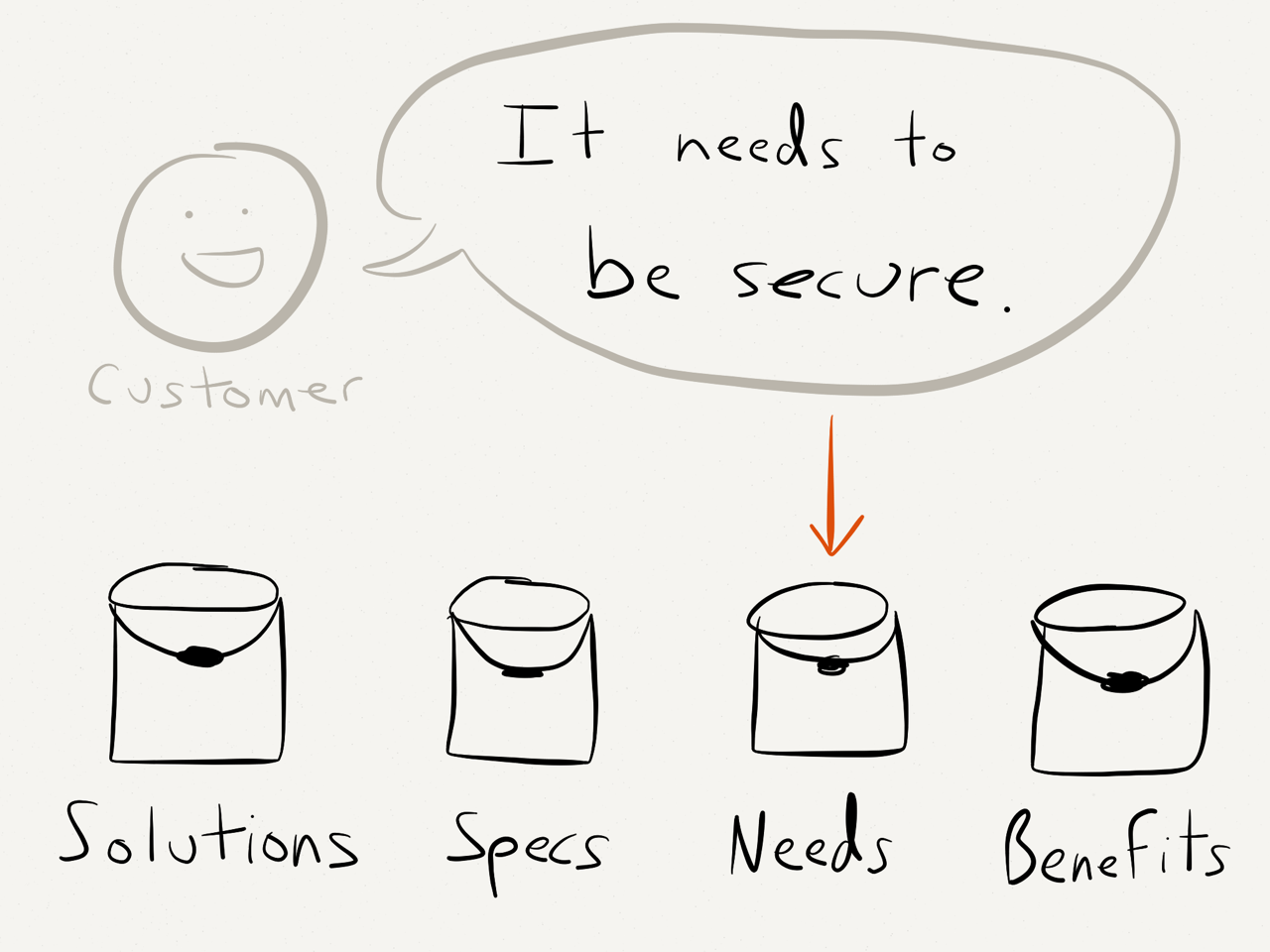

When you talk to customers, they don’t give you “requirements.” In fact, requirements don’t really exist; they’re not tangible in the real world. Instead, people make statements, and the statements they make can be separated into four buckets:

Solutions

Specs

Needs

Benefits

The sketches above give you an idea of what that sounds like. Usually, these statements aren’t directly actionable by the product team and need to be “unpacked” to some degree. You need to translate what you’re hearing into either:

Outcomes they’re trying to create

Goals they’re trying to achieve

Jobs they need to get done

Constraints they’re under (don’t forget these!)

There’s lots of information available on how to translate the statements into actionable insights: you can use Tony’s book, refer to The Jobs-to-be-Done Handbook, go with the Lean Startup approach, or use the traditional Cooper design methodology.

Talk to customers, but don’t take their statements at face value.

User Stories Must Die

I knew the traditional Agile user story was lifeless and disconnected from the real world long before I could articulate why. Then I came across Alan Klement’s post on replacing user stories with Job Stories, which builds on top of the Jobs-to-be-Done framework.

Instead of the usual “As a / I want / so that” structure, a Job Story looks like this:

- When [I’m in a certain situation]

- I want to [take some action]

- so I can [achieve some outcome].

I’m in the middle of synthesizing a pile of customer research right now, and I’m kind of amazed how well the Job Story lets me encapsulate what I’ve learned in literally one sentence. Traditional design methodologies offer other ways to capture and share these insights, but boiling it down that much is very compelling.

Another benefit I’m seeing is knowing how much more research is needed. That is, if you can’t write the Job Story to explain a behavior, you’re not done interviewing.

The Study of Causation: Etiology →

I was listening to the TED Radio Hour today and ran across a great word: etiology.

It’s the study of causation, as in:

What causes someone to contract polio?

For those of us doing product work, it’s critical to know what causes someone to use a particular feature. What caused this user to run a certain report? What’s causing these other users to create a given workaround?

Your product will improve when you understand the etiology of each user behavior.

Revolutionary Products, Existing Demand

Your product can be the newest, coolest thing around, but it still needs to serve existing demand in the market. Even the iPad was introduced by listing the activities people already do that it improved upon:

Web browsing

Email

Photo management

Watching video

Listening to music

Playing games

Reading eBooks

By itself, the list borders on mundane.

Ash Maurya, a leader in the Lean Startup community, made this great point on the latest episode of the Jobs-to-be-Done podcast. Check that out for more.

The Four Forces of Product Switching

“If only we could get more customers, this thing would really take off.”

Why hasn’t that happened yet? Well, it’s partly because no matter how cool your product is, there are forces conspiring against you.

The Four Forces

There are four forces at play when someone makes a decision to buy or use your product (shown above).

Many companies make an implicit assumption that if their new product has more/better features than a competing product, customers will transition to them. That’s simply not true; features aren’t nearly enough. You need:

Push: The consumer needs to have some problem or dissatisfaction with the solution they’re using now.

Pull: Your product needs to have a compelling feature set, ideally one that speaks to the problem they’re having.

To address Anxiety: Customers won’t implicitly trust you and your offering, and will worry about what bugs/issues they’ll run into.

To address Inertia: People have built up habits that will be hard to break. Installed base, existing integrations and behavior habits are all working against you.

Let’s step though an example to see how this works.

Switching from Android to Windows Phone

Microsoft realizes they’re behind in the smartphone race, and that many new users of Windows Phone will have to be former Android or iOS users. Android seems like the better target, with 22% of Android users surveyed in September 2012 saying they would switch to the iPhone 5 when it was released.

With this in mind, Microsoft released an Android app that scans what’s installed on your phone and recommends a substitute app for Windows Phone. In doing so, they’re addressing the forces of Inertia (“can I do what I’m used to with my phone?”) and Anxiety (“what will I be giving up?”).

So here’s one way the forces could play out:

Push: “This old Android phone as a very glitchy touchscreen.”

Pull: “Wow…this new Nokia is really elegant. It’s very smooth to go from screen to screen.”

To address Anxiety: “I wonder how good the reception is. I’ll keep an eye on that.”

To address Inertia: “Ah, perfect…I can still use Pandora to listen to music.”

If the Push and the Pull are greater than the combined Anxiety and Inertia, then the customer will switch from Android to Windows Phone. If not, they don’t switch. This example also illustrates how the forces play out differently for every individual.

Placing Your Bets

Even though each person experiences the forces in their own way, most of the time you will only release one product. So how do you position your offering for maximum switching?

The good news is, you will almost always see patterns in customer behavior (“everyone hates the glitchy screen”), and you can have some confidence you’re investing in the right areas. Even better, the patterns can emerge with less than 10 customer interviews. But the only way to tease out those patterns is by talking to customers.

You can’t rely on traditional market research, since it focuses on people’s feelings towards the product/brand and does not dive into usage patterns. Interviewing or observing customers is the only way to reliably map out the Push, Inertia and Anxiety your product will face as it enters the market. Don’t you want to know what you’re up against?

In Econ 101 terms, this comes down to understanding everything around the demand for your product. Framing this in terms of supply and demand also helps you see why you shouldn’t iterate your way through this problem. It’s wasteful to simply build something and obtain feedback, since that’s focusing on what you can supply instead of the demand. To gauge the demand, you can focus that more precisely. Figure out what people are doing now.

“Spaces” Don’t Exist

You can’t swing a dead cat at this year’s CES without knocking over a booth full of “wearable” technology. You’ve probably heard of Google Glass, but did you know you can also buy a drum machine t-shirt, solar-powered bikini and jeans with an embedded keyboard and mouse?

No doubt about it: wearables are one of the hottest “spaces” right now. I see only two problems:

- There is no such thing as a “space.”

- It doesn’t matter if the products are wearable.

Spaces Don’t Exist

The term “space” is a product of lazy, muddled thinking. I can’t say it better than Marc Andreessen:

There is such a thing as a market—that’s a group of people who will directly or indirectly pay money for something. There is such a thing as a product—that’s an offering of a new kind of good or service that is brought to a market. There is such a thing as a company—that’s an organized business entity that brings a product to a market. But there is no such thing as a “space”.

If someone tells you that “space” is hot, ask them who exactly will buy these products, and what hole it will fill in the buyer’s lives.

Categories Don’t Matter

Whether something like Google Glass is wearable may or may not be relevant to what it helps me do. Mat Honan spent the last year using Glass and identified some concrete usage for it. I’ll pick one example here and phrase it in terms of a job story (a term coined by Alan Klement):

When I’m with my child and (s)he does something cute, I want to take a photo quickly without retrieving a device so I can stay engaged while capturing the moment.

Couldn’t something like Dropcam with more advanced face detection perform this job? How about other products currently focused on security monitoring? It’s not important to me that the device doing the job be mounted to my head, as long as it gets done. In fact, I may prefer nothing on my face.

The interesting products from this year’s CES will address underserved jobs-to-be-done. They need not be attached to your body.

Functional, Social, and Emotional Jobs

Have you ever been watching a game show and found yourself screaming at the TV because you know the answer to the question, but the contestants don’t? That’s how I felt listening to a recent episode of NPR’s Planet Money podcast. It’s a great show that boils down complex economic issues like the European debt crisis into digestible narratives.

But on this one, they missed the boat.

The Topic: Labels

The topic of this particular episode was the effects of labels on product purchasing, starting with the example of generic pharmaceuticals. The story on generics asks why anyone would buy a brand name like Tylenol or Bayer instead of the generic version with the same active ingredients. The imprecise conclusion they report is the following: consumers waste money on a brand name when they lack information and don’t understand the goods are identical.

This is only true if you assume consumers evaluate products solely based on their function. In reality, every product has three components in the eyes of the consumer:

- Functional: As the name suggests, this is the core function the product performs for the consumer. (“How clean does the detergent make my clothes?”)

- Emotional: This is how the product makes the consumer feel. (“This detergent makes me happy because it reminds me of my childhood.”)

- Social: This is how the product affects the consumer’s relationship with other people. (“When people see the detergent bottle and notice it’s a ‘green’ product, I’ll look good in their eyes.”)

A product that costs more primarily due to emotional or social factors could also be called a luxury product. There may be some small functional differences between the Casio MQ24-1B2 and the Tag Heuer Monaco Calibre 36 but not enough to explain why the former costs less than $10 and the latter costs more than $10,000. They both tell time, but somehow Tag Hauer can charge 1000 times as much. Or, you can take a page from Apple’s book and sell a higher volume of affordable luxury items.

The lesson here for product teams is that if you want to charge more, focus on the emotional and social components. (Better that than becoming a commodity.) Despite the fact that you could email your friends photos of where you are, Facebook bought Instagram for $1 billion. And despite the fact that it’s easy to set up a free web site, Yahoo! bought Tumblr for $1 billion.

So how do you understand the emotional and social impact your product has on your customers? Simple: go talk to them. You need real stories of purchase and usage to get this right. And don’t forget this isn’t the same as market research…that focuses on feelings about the brand, whereas you need to access the feelings about the product.

Taking the next step

The method of analyzing a product by its functional, social and emotional components is another aspect of the Jobs-to-be-Done framework. You can learn more about this at the workshops hosted by Bob Moesta and Chris Spiek.

A template for Jobs-To-Be-Done: The Timeline

A Template for the Jobs-To-Be-Done Timeline

Clayton Christiansen is as high-profile as a business school professor gets, being the author of the only business book Steve Jobs ever read. And while his work on disruptive innovation has been hugely impactful, there’s another aspect of his work that any business can use: the Job-To-Be-Done.

Much has been written about Jobs-To-Be-Done Theory, but the core concept is simple: behind every product purchase is a certain “job” the buyer needs to get done. IKEA, for example, has had great success orienting its business around a consumer that needs one or more rooms furnished in a hurry. And there’s the classic story of a fast food chain discovered adults buying milkshakes as a drive time breakfast substitute. Understand the job and you’ll understand the demand for your product.

One of the best methods to identify the job your customers are looking to get done is to use The Timeline. The Timeline is an interview technique in which you step the interviewee through one particular instance of a given product being purchased and used. It begins with the first thought they consumer had they needed a product similar to the one they bought, extends through using the product, past the “honeymoon period,” and evaluating their satisfaction in retrospect.

Like any timeline, the Jobs Timeline has certain key points on it, and between those are phases. The following is a quick run-through of how to use the template and run one of these interviews.

Tip: When you sit down with your interview subject, set expectations by asking them to pretend you’re filming a documentary about this purchase. Your interview will be much more fruitful if you can “move their mind” back, so warm up with questions on where exactly they were, what the weather was like, and so on. Put them back in the past.

The First Thought is aptly named, and defines the beginning of the Timeline. It’s not a great place to start the interview, however. If you start at the purchase and work backwards, you’ll get much better information. If you simply ask people when they had the First Thought, they’ll answer the question multiple times, and each time this event moves backwards in time. This makes the interview feel choppy. Work backwards and you’ll get there.

“I liked my car when I bought it, but I remember one cold day it felt really drafty and I realized the mileage was getting up there.”

After the First Thought, the person goes into a Passive Looking mode. They’ll have their eyes and ears open for potential matches to their need. Jot down anything they noticed or remember relevant to the purchase during this time. Maybe they noticed an advertisement for a possible solution. (Note to marketers: this is a good time to advertise to them!)

Eventually, something happens that pushes the buyer into an Active Looking mode. This thing that happens is captured as Event 1. Capture this.

“My friend and I originally bought our cars around the same time, and he got stuck in the city because his wouldn’t start.”

In this phase they may compare options online, read books or magazines, and ask friends about the issue. They’ll generally expend much more effort investigating the options. The options the consumer identifies are known collectively as the Consideration Set. This is your competition, so ask about this. Make notes on what they compared, and how. You’ll probably be surprised how products “outside your category” are in the running in the mind of the consumer. (Customers don’t care how you’ve segmented your market.)

More time passes, and sooner or later another event happens (Event 2) that causes the buyer to set a deadline for the purchase. Jot this down as well, and look for patterns among buyers.

“When we saw the check engine light on our car, we knew we’d be going to dealerships that weekend.”

During this Deciding phase, the consumer makes Trade-offs among the criteria they identified earlier. Capturing these trade-offs is critical, since it gives you real insight into what your buyers think is important. Record how the buyer ranked them. Cost over quality? Speed of delivery? What actually mattered?

Before long, the consumer makes the Purchase and simultaneously sets their own expectations about what it’ll be like to use the product. The Consuming period after the buy is a continual evaluation against those expectations. Capture which item they ended up purchasing, and prepare for the interviewee to flood you with details on what it was like to use the product and whether they were satisfied.

Satisfaction surveys tend to focus on the buyer Looking Back at this point and reflecting on their purchase. If the interviewee purchased your product, you may get a few good nuggets of info in this satisfaction discussion. Outside of that, satisfaction reports are overrated because value is defined in the customer’s mind Going In as part of the steps leading up to the purchase. Understanding how the buyer built up their definition of value is usually much more valuable from a strategic perspective. Put another way, understanding how well a product met a certain consumer demand is not the same as understanding the demand itself. Don’t make the mistake of confusing the two.

After the Interview

Even a handful of these interviews will get you deep inside your customers’ heads and fill in your understanding of what they’re trying to get done. Armed with that information, you can build new features or create entirely new products that address a demonstrable need. Minimally, you can tweak your product’s marketing to make sure you’re truly speaking to customer concerns.

Tools like these that build an understanding of the customer are critical for product teams. Without them, they’re simply flying blind—guessing what current customers value and what would attract new ones. Do a few of these interviews and share the results with anyone that touches your product. If departmental silos have hardened in your organization, try the sledgehammer of customer insight.